University has meant that a big portion of the free time I used to have is not there anymore. Still, a lot of very important features have been developed, and I believe OSPGL may be playable by the end of this year. In this blogpost the most important changes will be presented, alongside some plans for the future!

Physically Based Rendering (PBR)

The biggest and shiniest feature that has been implemented in the last two years is PBR. The "detonator" for this change was the dropping of assimp as an asset loading library in favor of the gltf format, alongside the tinygltf library.

After quite a bit of work, assimp was replaced and the PBR renderer came into existence.

There's currently a bug that I've been struggling to find during the rendering of normal maps on parts. There are some seams that are probably caused by messing up the coordinate system math. Otherwise, the system seems to work really well and gives good results:

Environment Mapping

One of the most important parts of a PBR renderer is the support of environment maps. Without those, PBR rendering looks extremely bland. Environment maps are similar to traditional skyboxes, they are basically an image which "wraps" around the scene, lighting up objects. Without delving too deep into implementation details, they allow an object to receive light from all directions, correctly simulating the physical composition of the surface using a roughness and a metallic parameter. The easiest approach to roughness is to generate a "reflection map" and then blur it progressively for rough surfaces.

The huge problem is that, in OSPGL, the environment is almost never static. The only places where a static environment map can be used is in the editor scenes, as during flight the vehicle is moving, potentially at very high speed, through a wide variety of environments: From the dark shadows of the Earth to atmospheric flight, high up above planets, near the surface, or even in interplanetary space.

One solution would be to use a variety of environment maps for different situations. For example, when flying in the atmosphere we could use a simple skybox with generic ground below. This solution breaks down the moment you gain enough altitude as for the atmosphere to start fading away. Suddenly, everything is black except for the ground below, which must be represented reasonably accurately in the enviroment map for the scene to make visual sense. (ie, if you are flying above a desert and the blue sea is reflected the scene will lose visual coherence)

The other solution, and the one I decided to implement, is to generate the environment maps in realtime from the scene. This is done in some "traditional" games using reflection probes to allow dynamic reflections of the scene into objects, but the effect is usually not extremely noticeable as the static environment will still represent most of the lighting contribution.

In a space game like OSPGL, this kind of effect is extremely important if decent graphics are desired. A simpler solution, such as KSP's mod PlanetShine can give a very good looking result, specially when combined with great 3D models and texturing, and maybe some true reflection probes (as spacecraft tend to be quite reflective!).

The method used in OSPGL is basically using reflection probes, but also generating environment maps from them to accurately light up objects. In fact, traditional lights are actually not neccesary in this system as a bright object, such as the sun, will change the environment map in a very realistic way, offering easy area lights (although only if they are really far away from the object being lit up).

The effect is really good as can be seen in the comparison photos, achieving semi-realistic results even with fairly crude models and textures.

In terms of perfomance, the effect is fairly expensive, and requires a relatively modern GPU to run at good framerates. It can be disabled, or tuned to generate the environment maps less frequently, although great optimizations could be done in the future.

Planet Surface Textures

Having textured surfaces is another must-have, as otherwise the planets will look plastic-like, and overall ugly, specially near the surface. This effect works specially well to render craters and other smaller details.

There are, currently, two layers of texturing to each planet. First, there's a global map which covers the whole planet, and can be used to give better detail to space scenes without having to increase the detail of the planet mesh. Second, there are local textures, applied using triplanar mapping which allow detail texturing of the surface. Currently, a single texture is applied to the whole planet, but it should be straightforward to implement per-biome texturing.

Triplanar Mapping

Tipically, 3D objects are textured by using what's known as UV maps, which basically map each polygon of the object to a region in a 2D texture. This method is very appropiate for manually modelled meshes, but fails quickly on procedural objects, and is specially ill-suited for terrain. Triplanar-texturing is very appropiate for terrain, and consists on applying different textures on the "vertical" direction and "lateral" directions.

One of the greatest challenges during the implementation of this technique was obtaining the up and lateral vector. Obviously, there's no universal up direction in the surface of a planet, so this vector had to move around with the camera. But it's important that the vector moves in quantized steps, as otherwise the textures would seem to follow the camera around instead of being actually attached to the ground. After a bit of brain melting coordinate space translations, I finally managed to get the textures to stick to the ground. There are a few artifacts here and there, specially in the lateral direction's normal maps, but it seems to work quite well for now.

In terms of performance, the effect is very lightweight and runs pretty well even on low-end PCs and integrated graphics.

New Atmosphere

A new atmosphere shader was written, as introducing the new PBR renderer, including gamma correction, made the old model look a bit weird. This new shader uses real physical scattering, and is heavier on the GPU than the previous version, so the old shader has been left as an option so low-end PCs can use it.

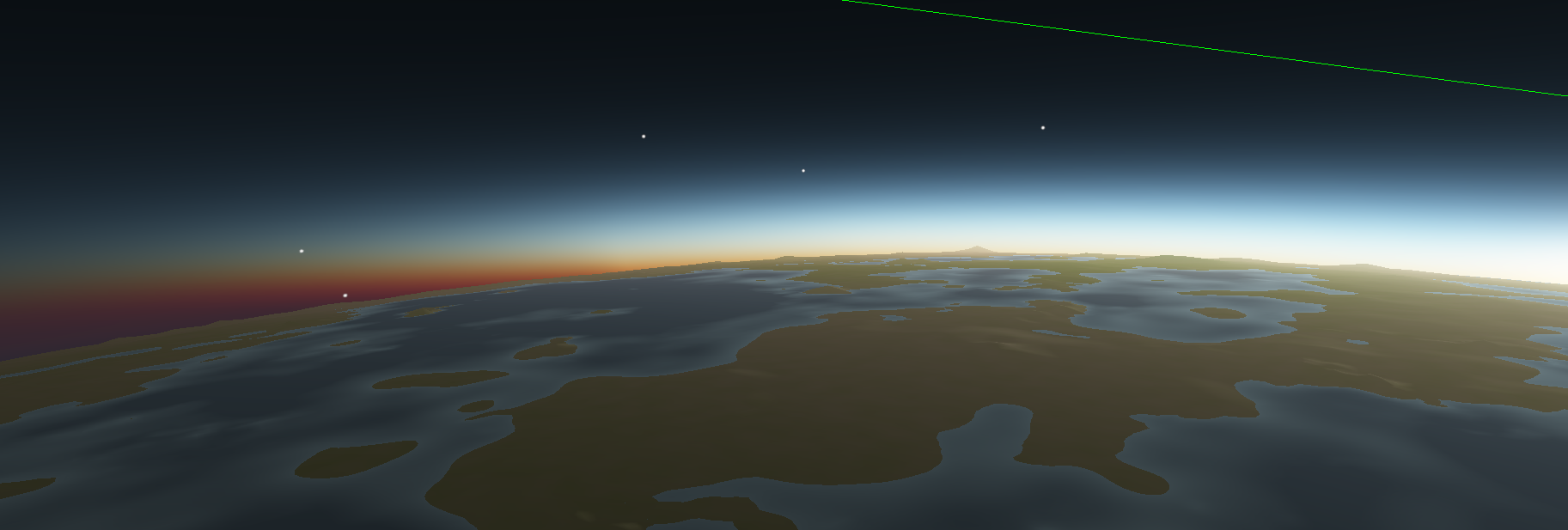

This new atmosphere shader also features beautiful sunsents:

N-Body Physics for Planets

I decided that using Kepler orbits for planets was a mistake, specially on the perfomance side. Simulating the whole N-body system (or probably only meaningful interactions) is, surprisingly, cheaper than trying to solve Kepler's equations every timestep for vehicles. This will also allow a more realistic propagation of system elements without needing correction factors, but increases the difficulty of designing custom, stable systems.

Plumbing

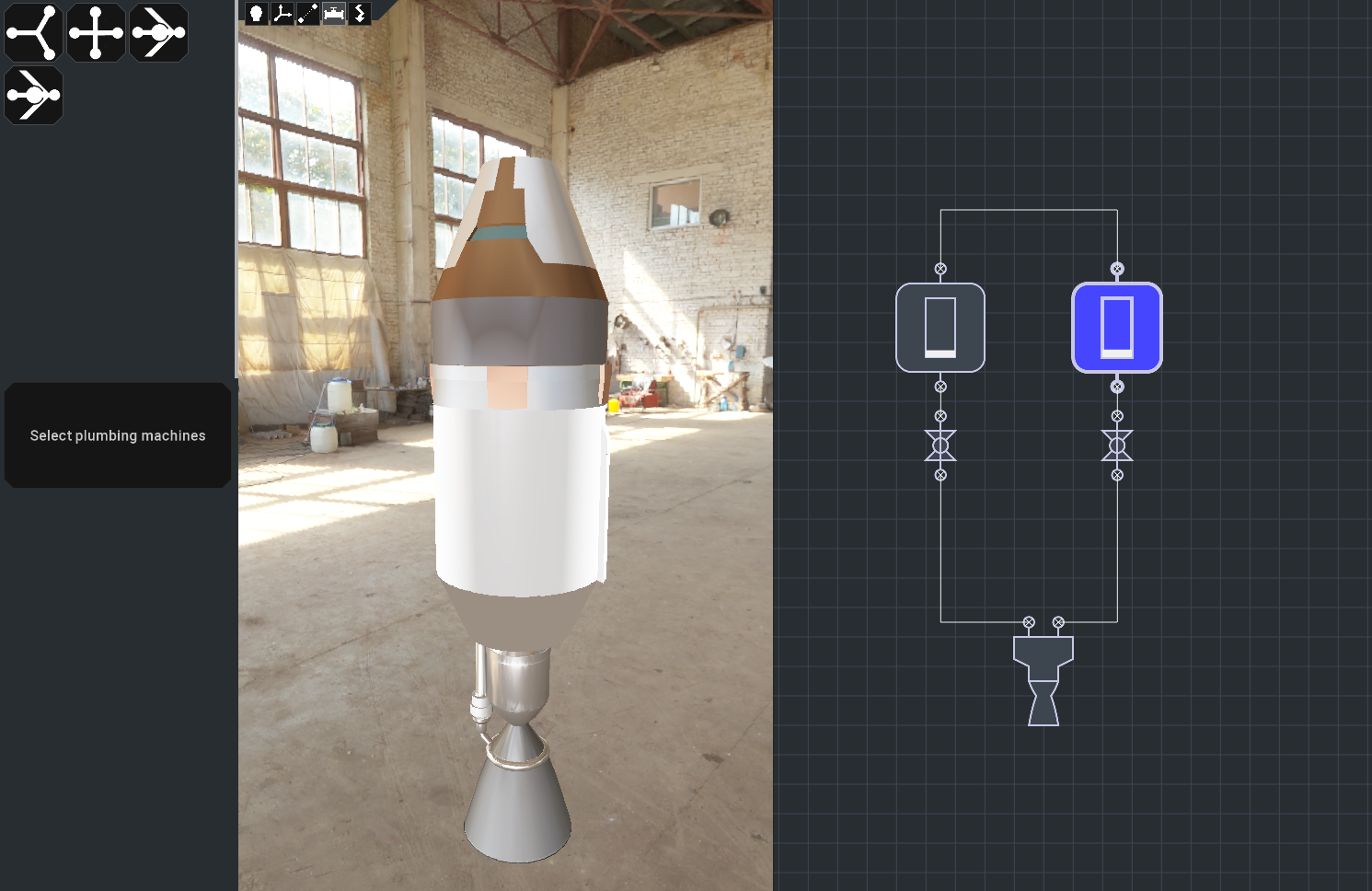

One of the features I want OSPGL to have is a detailed simulation of the internal plumbing of rockets. The justification is that this plumbing system will allow users to build very complex cockpits and systems to interact, mostly, with the plumbing system. (Other detailed systems are also in my mind, such as radio or electricity).

The plumbing system consists of a graph of fluid ports, connected by pipes. There are two types of fluid ports in this system, "true ports" and "flow ports". The later are ports which modify the state of the flow (pressure), but hold no significant ammount of fluid internally and thus are not boundary conditions for the system: Their behaviour depends mostly on what's flowing through them. "True ports" specify their port pressure, which doesn't depend on external conditions, and are the boundary conditions of the system.

The solver goes from true port to true port, simulating any flow ports found in the path, to build a flow map that determines which true port will drain and which one will accept fluid, and in what quantities. Right now, there's not really any code to handle a machine being overfilled, but this is being worked on.

This design was the result of many months of thinking, struggling to find something which offered acceptable perfomance (not a true fluid simulation), decent realism, and, more importantly, good user interaction. The idea came to be, as it's usual, on the least expected moment as I was doing some differential equations for university.

Another must-have feature that's implemented is linear flow. This means that if a pipe is filled with, say, triethylborane (TEB), this material will reach the engine before the fuel that's being pumped into the pipe, and thus allow ignition systems based on pre-filling of a pipe.

I'm still thinking on how to make this system more tunable to allow a less realistic mode of operation that's more similar to KSP's fluid flow for players who don't want to get too detailed with their rocket plumbing. One option to implement this feature would be to disable pressure calculations in pipes so all connected systems can share fluids, without the need of pump usage or similar, although this would require code changes to all machines.

Materials

Another important feature is the (physical) material system. This material system is going to be used both for fluids (gases and liquids in the plumbing system) and the solids that make up parts. Materials in the liquid and gas phase can react using the chemical reaction system, which simulates chemical equilibrium and activation energy for a series of reactions specified in TOML files.

Right now the system is being developed to work in the combustion chamber of rocket engines, hopefully approximating decently real life values. Also, another advantage of the material system is that exhaust products can be simulated, and rendered, accurately. Ignition processes could expell non-reacted fuel, we could simulate the green flame characteristic of boron compounds in the hypergolic starter, etc...

This change may, or may not, be motivated by my recent obsession with chemistry ;)

Fuel Tanks

This is one of the first parts of OSPGL to be implemented fully in Lua, and thus could easily be changed by any player willing to adapt the game to other styles. Right now, fuel tanks fully simulate liquid-vapor equilibrium, enabling interesting concepts such as liquefied gas storage, or pressurization with inert gases. This feature was surprisingly easy to implement, and offers a lot of real life engineering decisions that will need to be made by players.

Tanks have two outlets, one situated "on the top", which, under gravity conditions allows draining of gases, and another one "on the bottom", which would allow drainng only liquids. Obviously, this will only work if the fuel tank is experiencing acceleration in the correct direction. This behaviour is simulated using a "ullage factor". The greater this value is, the greater the mixing of liquid and vapor in the tank, and thus draining processes will drain a mixture of both (implemented using a pseudo-random perlin noise). This instantly simulates the need for ullaging as otherwise the engine will very likely fail to start or be damaged from vapours being pumped instead of liquids. (An explosion could happen in the combustion chamber, pumps could break, etc...) Another feature is column pressure: If the rocket is experiencing acceleration, the pressure on the "bottom" port will be greater than that in the "top" port because of the weight of the fluid column.

Future

I can give an small overview of what's planned, related to the features exposed before. Obviously many more features are planned, mostly on the gameplay side: Map view, maneouver planner, ISRU, etc... A lot of these are probably going to be implemented in lua as the game engine becomes more and more mature, so it's interesting to delay their implementation.

It's very likely that some of the parts currently implemented in C++ will have to be rewritten as lua code, or atleast exposing the functions needed to do so. This way, modders will have great access into the game without needing to recompile it. One good example is the editor, which, looking back, should have been implemented in lua. Another one is the plumbing editor (one could expand this thinking to the whole plumbing system).

In order to save some precious development time, I'll probably just try to expose all functions needed to implement them in Lua, but actually keep it in C++, giving an option to disable it.

This is the result of not having a clear vision of where OSPGL ends and where do mods begin, but hopefully will not result too damaging! I'm trying to get to a playable game reasonably quickly, but it's also a good idea to try to get a base engine which can be used for other kind of games, while not really being a general purpose game engine to avoid wasting too much time on features useless for OSPGL.

Optimization of Environment Mapping

One of the biggest problem of the environment map generator is that it needs to render the whole scene 6-times. Rendering the scene is quantized: it must be done all at once on the GPU. If a partial render of the scene could be done, the environment map could be generated over the course of many frames, reducing the perfomance impact in exchange for potential seams in the reflections. This is already partially done, as the system can be tuned to render the scene only once per frame, instead of the 6-renders each frame, and the seams are barely noticeable unless moving at great speeds near a planet surface.

I need to investigate wether it's possible to do partial renders, and wether it actually performs better or worse. There are probably many ways to optimize this as the GPU will be handling the same data both for the env-map render and the normal scene render.

Another big optimization would be to use lower detail models for the environment maps passes, although this is surprisingly complicated, specially near planet surfaces, as it can happen that, when using lower detail planet surfaces, a point that used to be above-ground becomes under-ground, breaking rendering as the interior of the planet will be seen in the reflection map. Maybe we can get away with rendering only the nearest surface tiles to the camera, or something similar.

Simplified Environment Maps

For low end PCs, instead of only giving the option of disabling the effect completely, or tunings its frequency down a lot, a system could be implemented which renders the scene geometry in a greatly simplified manner. For example, planets could become a colored ball (textured, or flat color), and atmospheres a simple gradient. This effect should be cheap enough to run at high FPS in old integrated GPUs, the most expensive part would be blurring the reflection maps.

Environment Mapping for Space Objects

The current environment map generator doesn't work well for lighting up planetary bodies as the cubemaps are generated from the camera. In space, it's quite common to see bodies being lit by reflections of other planets: Moonlight is a great example.

To implement this kind of effects, another pass would be required. A cubemap could be rendered from the origin of each planet at a very reduced interval (in some cases, it could only happen a few times during the playtime), and then the environment map generated applied to that planet. A lot of thinking needs to be done on how to handle this effect when the player is landed on the planet, for example, to allow reflections of a moon on the surface.

Semi-Procedural Planets

The surface texturing system, specially the global map, seems to conflict with the idea of procedural planets. And this is a very real concern. The solution that's planned is to have semi-procedural planets, allowing both an increase in performance and surface detail, at the cost of a one-time baking step. The mixed model would imply the tiles being baked up to certain depth and stored on the disk as meshes. The lua code that generates surfaces would have a baked section, that generates big scale details, and a realtime section, cheaper, to add close up details.

This will allow really complex planet surfaces as there will be no real limit to the number of noise generators used during the baking phase. Close up surface details will also benefit greatly as all the computing power used previously for the global maps is now available for small details, such as craters.